The Complete Cresthaven Adventure Design Guide

Creating adventures is what separates good DMs from great ones. A solid adventure provides structure without railroading, challenges without frustration, and memorable moments that drive the campaign forward. This guide teaches you to think like a story architect, building adventures that span multiple sessions and locations.

Think in Scale: Adventures are story arcs (macro), dungeons are locations (meso), encounters are individual scenes (micro). This guide focuses on the big picture: multi-session stories with clear goals, escalating complications, and meaningful consequences.

Campaign Integration: Every adventure should either close a door or open a new one in your campaign. Adventures are stepping stones in a larger story, not isolated episodes. Each one should leave the world changed and create seeds for future conflicts or opportunities.

The Foundation: Goals with Teeth

Give your players a goal with teeth. Vague objectives lead to aimless wandering. Sharp goals keep everyone moving forward and create natural story momentum.

Your goal should be specific enough to drive action but flexible enough to accommodate player creativity. “Stop the goblin raids” beats “deal with the goblin problem” because it suggests both the threat (ongoing raids) and the victory condition (stopping them). It leaves room for negotiation, elimination, misdirection, or discovering the raids’ true purpose.

From Goal to World

A clear goal generates content naturally. Take this example: eliminate the werewolf terrorizing the town. This single objective immediately suggests:

Locations: The town becomes your primary stage, but you’ll need the werewolf’s lair, crime scenes, and perhaps the surrounding wilderness. Multiple locations, not just one dungeon.

NPCs: Townsfolk who might be the werewolf, victims with clues, witnesses with conflicting stories, officials who help or hinder. Each serves the central goal.

Complications: The werewolf’s human identity creates moral complexity. Silver weapons are expensive. Town guards don’t believe in werewolves. The next full moon approaches.

Stakes: People die every night the werewolf survives. The town might evacuate. Someone important to the characters could be next.

One sharp goal spawns an entire adventure naturally. Weak goals force you to invent obstacles from nothing.

Adventure Seeds: Starting Points for Stories

Adventure seeds are brief concepts that spark full story arcs, not single encounters. They should suggest multiple sessions of play, various locations, and meaningful character choices. Here are examples organized by core dramatic structure:

Protect and Defend

- A corrupt warlord harries a village the characters have sworn to protect

- An isolated village seeks heroes to defend against nightly monstrous attacks

- Undead forces mass to assault an old monastery protecting a sealed evil artifact

- A floating fortress from another dimension crashes, spilling hostile forces into nearby lands

Uncover and Explore

- Dwarven explorers uncover a mad wizard’s vault filled with dangerous experiments

- The corpse of an old god, infested with devils, appears embedded in a mountain

- A supernatural plague from forgotten ruins spreads, and its source must be found

- Forbidden knowledge from an old book brings powerful entities seeking to eliminate witnesses

Hunt and Destroy

- A fledgling apprentice releases a demon who begins building a fiendish army

- Dragon blood is needed to cure a plague, requiring a hunt across dangerous territory

- Orc raiders have enslaved dwarves to dig into ancient ruins for dark purposes

- A werewolf terrorizes a town, but its human identity remains hidden

Recover and Steal

- A wizard hires the party to retrieve an ancient artifact from hostile territory

- The local mayor’s child has been kidnapped by unknown forces

- Rivals race to claim treasure from a newly discovered ruin

- Stolen crown jewels must be recovered before the kingdom’s legitimacy crumbles

Survive and Escape

- A cursed land traps travelers, slowly draining their life force

- The party awakens in an enemy stronghold with no memory of how they arrived

- A magical disaster transforms familiar territory into hostile, alien landscape

- Political upheaval forces the characters to flee their homeland

Each seed contains enough scope for multiple sessions, various locations, and escalating complications. They provide direction without dictating specific solutions.

Types of Adventures

Understanding different adventure types helps you structure story arcs and manage player expectations across multiple sessions. Most adventures combine elements from multiple types.

Delve Adventures

Core Element: Objective-based story arcs in contained locations.

These adventures focus on a specific location: the haunted castle, the dragon’s mountain lair, the wizard’s tower. The entire story arc revolves around reaching, exploring, and achieving goals within this space. Success comes through preparation, resource management, and overcoming the location’s defenses.

Strengths: Clear boundaries and objectives, natural progression, satisfying exploration. Best For: New players, groups that enjoy tactical challenges, adventures with clear endpoints. Story Arc Tips: Build the location’s reputation before characters arrive. Create multiple reasons to explore different areas. Plan what happens if characters leave and return later.

Survival Adventures

Core Element: Resource management and time pressure across multiple sessions.

The environment itself becomes the primary antagonist. Characters must manage food, water, shelter, and safety while pursuing their goals. Scarcity creates tension as every resource expenditure becomes a meaningful decision.

Strengths: Natural time pressure, meaningful resource decisions, immersive tension. Best For: Experienced players, longer story arcs, wilderness or hostile environment settings. Story Arc Tips: Establish clear limitations early. Make the environment feel actively hostile, not just inconvenient. Make expenditures meaningful to the larger goal.

Cat and Mouse Adventures

Core Element: Ongoing pursuit or escalating threats across multiple locations.

Something dangerous actively hunts the characters or responds to their actions. This might be an intelligent enemy, spreading disaster, advancing army, or magical curse. The threat adapts and escalates based on character choices.

Strengths: High ongoing tension, reactive storytelling, cinematic feel. Best For: Groups that enjoy suspense, experienced DMs comfortable with reactive planning. Story Arc Tips: Give the threat clear capabilities and limitations. Provide ways for characters to gain advantages or slow the threat. Vary pressure with breathing room.

Intrigue Adventures

Core Element: Webs of NPCs, shifting allegiances, and hidden truths.

Success depends on managing relationships, gathering information, and navigating complex social situations. The “dungeon” is a network of people with competing interests, hidden agendas, and changing loyalties.

Strengths: Heavy roleplay focus, complex problem-solving, memorable NPCs. Best For: Roleplay-focused groups, politically minded players, urban settings. Story Arc Tips: Create multiple factions with conflicting goals. Make every NPC want something from the characters. Prepare backup ways to reveal crucial information.

Journey Adventures

Core Element: Travel across dangerous territory with mounting challenges.

The adventure is the journey itself: crossing hostile lands, navigating treacherous terrain, or following ancient routes. Distance, attrition, and encounters along the way create the story’s tension and pacing.

Strengths: Natural pacing, variety of encounters, sense of exploration. Best For: Sandbox campaigns, world-building focused DMs, groups that enjoy exploration. Story Arc Tips: Make the destination worth the hardships. Vary encounter types and difficulty. Create decision points about routes and rest stops. Include opportunities to turn back or take detours.

The Adventure Checklist

Test your adventure design against this checklist. Strong adventures include most or all of these elements at the story arc level:

Essential Elements

- Clear Goal: A specific objective players can understand and pursue

- A Prize Worth Pursuing: Treasure, knowledge, freedom, or power that justifies the risk

- Memorable NPCs: Characters who drive the story forward through their needs, secrets, and relationships

- Threats that Escalate: Dangers that grow worse over time: spreading plague, advancing armies, strengthening curses, or rival factions gaining power

- Opportunities for Player Agency: Multiple approaches to problems, meaningful choices with consequences

Story Architecture

- Escalating Complications: Problems that build on each other, forcing players to adapt (consider using the Tension Pool mechanic)

- Consequences for Success and Failure: Clear stakes that matter to characters and world

- Multiple Paths Forward: Different routes to the goal that respect different character strengths and player preferences

- Personal Investment: Reasons the characters care about the outcome beyond simple reward

Engagement Elements

- Information Gaps: Mysteries that drive investigation and discovery

- Time Pressure: Deadlines that force action over endless planning

- Moral Complexity: Situations where the right choice isn’t obvious

- World Impact: Changes that persist beyond the adventure’s end

Each element serves the adventure’s scope. Goals provide direction across sessions. Escalating threats create ongoing tension. Memorable NPCs drive roleplay and provide information. Personal investment ensures characters care about outcomes, not just rewards.

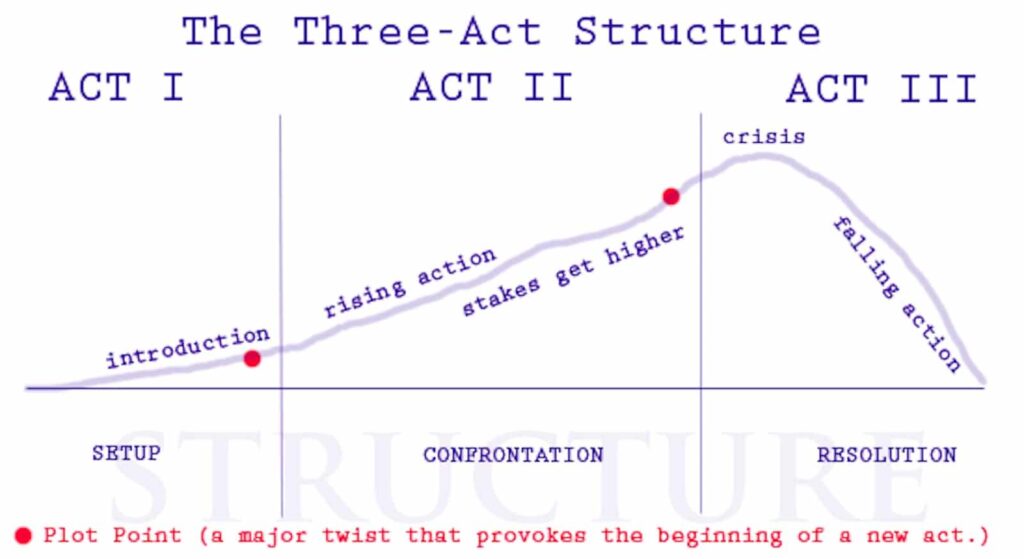

Three-Act Structure

Most satisfying adventures follow a classical three-act structure that creates natural story momentum and emotional satisfaction.

Act I: Setup (25% of adventure time)

Purpose: Establish the world, introduce the goal, and present initial obstacles.

The opening act should accomplish several tasks efficiently:

- Hook the Players: Present the initial problem or opportunity in compelling terms

- Establish Stakes: Make clear what happens if they succeed or fail

- Introduce Key Elements: Important NPCs, locations, or concepts they’ll encounter later

- Provide Direction: Give players enough information to make meaningful choices

- Set the Tone: Establish whether this is heroic, gritty, mysterious, or comedic

Common Structures:

- Crisis Opening: Begin in the middle of urgent action requiring immediate response

- Patron Meeting: Characters are hired, requested, or recruited for a specific task

- Discovery Opening: Characters stumble upon or investigate something unusual

- Personal Stakes: The goal directly affects someone or something the characters care about

Design Tips: Start with action or important decisions rather than lengthy exposition. Give players agency immediately. Establish the central conflict quickly. Foreshadow later complications.

Act II: Development (50% of adventure time)

Purpose: Escalate the conflict, develop complications, and test the characters.

The middle act contains most of the adventure’s content. Progressively raise stakes while providing multiple challenges. Use a pacing mechanic to escalate complications that make simple solutions impossible.

- Escalating Obstacles: Each challenge should build on previous ones, not just be harder

- Layered Complications: New information complicates the obvious solution

- Resource Taxation: Every adventure should tax resources: whether treasure, allies, reputation, or time. Make choices feel weighty

- False Solutions: Apparent successes reveal larger problems underneath

- Character Moments: Give each character spotlight time and difficult choices

Common Complications:

- The Real Enemy: The obvious threat serves someone more dangerous

- Divided Goals: Character or NPC objectives come into conflict

- Time Crunch: Deadlines force action over careful planning

- Moral Costs: Solutions require sacrificing something important

- Unexpected Allies: Former enemies become necessary partners

Build toward the climax gradually. Avoid flat difficulty curves by varying challenge types. Complications should emerge from the story naturally, not feel imposed by arbitrary mechanics.

Define success, failure, and walk-away outcomes before play begins.

Act III: Resolution (25% of adventure time)

Purpose: Resolve the central conflict and deliver satisfying conclusion.

The final act brings all story threads together in a climactic confrontation or resolution. Everything players learned and every choice they made should matter here.

- Final Challenge: The most difficult obstacle, requiring everything learned earlier

- Character Agency: Success depends on character choices and actions, not dice luck

- Consequence Resolution: Address all major story threads from earlier acts

- Emotional Payoff: Reward character investment with appropriate consequences

- World Shifts: Show how NPCs, factions, and the environment change based on the outcome

- Future Hooks: Plant seeds for future adventures without overshadowing current success

Resolution Types:

- Combat Climax: Final battle against the primary antagonist

- Social Resolution: High-stakes negotiation or political maneuvering

- Environmental Challenge: Racing disaster, collapsing stronghold, or magical catastrophe

- Revelation Climax: Final truth that recontextualizes everything

- Moral Choice: Decision that determines the adventure’s ultimate meaning

Make the climax feel earned. Give all characters important roles. Avoid introducing new rules during climactic scenes. Plan for both success and failure outcomes: players should face meaningful consequences either way.

Example Adventure Spine

Here’s how macro-level planning looks in practice:

Goal: Stop the mooncut cult from opening the gate. Act I: Hook via missing pilgrims; meet Abbot and City Watch; clue trail leads to three sites. Act II: Choose site order; faction pressure from Watch vs. Cult; rival adventurers seize a key; deadline advances as eclipse approaches. Act III: Gate ritual at cliff-temple; choice to shatter relic or bargain; fallout seeds next arc with surviving rival.

This demonstrates thinking in story beats without sliding into room design. Each act has clear purpose, multiple complications layer together, and the resolution creates new story possibilities.

Failure as Story Driver

Failure shouldn’t end the story: it should change it. This principle separates great adventures from mediocre ones. When characters fail to achieve their goals, the world responds logically, creating new opportunities and complications.

Types of Meaningful Failure

Partial Success: Characters achieve part of their goal but at significant cost. They save the town but the villain escapes. They recover the artifact but lose a valuable ally. Progress continues, but the path forward becomes more difficult.

Pyrrhic Victory: Characters succeed but the cost changes everything. They stop the plague but had to burn half the city. They defeat the dragon but it was protecting something worse. Success feels hollow and creates new problems.

Delayed Consequences: Characters succeed in the moment but their methods create future complications. They ally with questionable forces, use forbidden magic, or ignore collateral damage. The bill comes due in later adventures.

Planning for Failure

Always ask: what happens if the characters fail? The answer should never be “the campaign ends.” Instead:

- Escalation: The threat grows stronger or spreads further

- New Players: Other factions respond to the changed situation

- Changed Stakes: Success becomes harder but more urgent

- Alternative Paths: New approaches become necessary or available

Failure should feel meaningful, not arbitrary. Characters should understand why they failed and what they can do differently. The world should respond logically to their actions and inactions.

Advanced Techniques

Red Herrings and Misdirection

Don’t waste your players’ time with dead ends. A false clue is only useful if it makes the truth juicier when revealed. Use red herrings to complicate solutions, not stall progress.

- False Suspects: NPCs who seem guilty but reveal deeper truths when investigated

- Misdirection: Information that’s technically accurate but points to wrong conclusions

- Apparent Solutions: Obvious answers that work temporarily but create bigger problems

- Conflicting Sources: Multiple NPCs with different versions of events, each partly true

Every red herring should feel logical and important when first encountered. Give subtle hints that distinguish misleading information from genuine clues. Players should feel clever when they spot the deception, not frustrated that they wasted time.

Handling Unpredictable Players

Players will derail your carefully planned adventure. This isn’t a failure: it’s the game working as intended. Prepare for chaos by building flexible scenarios, not rigid scripts.

Modular Preparation:

- Design encounters that work in different locations (move the ambush to wherever they go)

- Create NPCs with clear motivations that drive behavior regardless of circumstances

- Know your factions and power structures well enough to improvise consistently

- Prepare more locations and characters than you expect to need

Adaptive Techniques:

- Say “yes, and…” to player ideas that improve the story

- Change unseen details to accommodate player theories that enhance drama

- Adjust difficulty based on current resources and party engagement

- Move important information between NPCs if players avoid your planned sources

Nothing exists until you describe it. Use this to your advantage.

Campaign Integration

Single adventures work best when connected to larger stories and persistent consequences:

Recurring Villains: Enemies who escape, learn from defeats, and return more dangerous. Let them succeed occasionally to remain credible threats.

Escalating Factions: Organizations that grow in power, influence, and complexity based on character actions. Allies today might become rivals tomorrow.

World Events: Things that happen whether characters intervene or not. Wars continue, seasons change, disasters strike. The world doesn’t wait for the party.

Persistent Consequences: Character choices should ripple forward. Towns remember their saviors and their failures. Political decisions create new allies and enemies. Magical experiments have lasting effects.

Plant seeds for future adventures in current ones: mention distant threats, introduce minor NPCs who might become important, hint at larger conspiracies. The best campaigns feel like living worlds where every adventure matters.

Design Philosophy

Remember these principles throughout your design process:

Player Agency: Always provide meaningful choices. Even when leading players toward specific goals, give them multiple ways to achieve those goals.

Consequences: Character actions should matter. Success and failure both create new situations that drive future stories.

Consistency: Your world should operate by consistent rules. NPCs should have logical motivations. Events should follow naturally from previous events.

Preparation vs. Improvisation: Prepare thoroughly but hold plans lightly. The best adventures emerge from the interaction between your preparation and player choices.

Fun First: Rules serve the story, and story serves fun. When mechanics create boring or frustrating situations, change them. When strict adherence to your plan reduces player enjoyment, adapt.

The best adventures feel like they emerged naturally from the world and characters rather than being imposed by the DM. They provide structure while rewarding creativity, challenge while maintaining hope, and complexity while remaining comprehensible. Your goal is not to tell a predetermined story, but to create the conditions where great stories can emerge from play.

Online Resources You Should Read

- https://geekandsundry.com/how-to-write-the-best-dd-adventures-ever/

- https://www.studiobinder.com/blog/three-act-structure/

- https://dnd.wizards.com/articles/features/building-adventures

- https://theangrygm.com/angrys-amazing-adventure-templates/

For more GREAT ideas as well as a “well worth the money” e-book the Lazy Dungeon Master visit: http://slyflourish.com/lazydm/